Over the holiday break, I reviewed the 5 conversations that Jesse and I have conducted with truly senior design executives for our podcast Finding Our Way, looking for lessons that could be distilled and imparted for those who aspire to such roles. As I pored over the transcripts, an overarching theme emerged:

Design leadership is change management.

This was actually stated in the first interview, by Katrina Alcorn, GM of Design for IBM:

“Well, I think if design was fully understood and recognized and invested in and respected, the way, for example, development is, we would not need to be change agents. We would need to be good stewards… I think we’re change agents because all of us doing this are still part of a movement to change how businesses work, how they run.”

In my thought partnership work with design leaders, I’ve at times encouraged ‘change management’ tactics to help them with specific initiatives. What reviewing these discussions with successful leaders made clear is that change management isn’t a tactic—it’s the job. And that other leaders would realize greater success if they framed their efforts with this perspective.

Thankfully, these leaders also shared the mechanisms by which they’ve enacted change. Analyzing these discussions, I distilled a set of practices and a mindsets that should help anyone trying to establish design as an active participant within their organizations. While I won’t claim this as some kind of magic key to unlock success, I would encourage using it as a playbook that scaffolds your efforts.

A. Shape a vision

B. Adopt a portfolio approach

C. Manage the relationships

D. Communicate with intent

E. Maintain patience and perspective

A. Shape a vision

To lead requires vision. At minimum it’s an orientation, pointing the team in the right direction. Even better, it’s a destination to which people are being led. Visions come in many forms. They could be mindset shifts (becoming more “customer-centered” or “experience-led”), process evolution (adopting dual-track agile, user-centered and inclusive design methods), or outcomes that show impact (adopting metrics like Google’s HEART framework).

North Stars

And, being designers, a common type of vision is the North Star, a concrete depiction of an improved future-state offering. As Greg Petroff stated, “You use a north star to drive the art of the possible…, to scratch the itch on tough questions… Artifacts are … tangible and easier for people to…identify with.” For Daniela Jorge, North Stars “make it feel real so that everyone can get aligned around that same outcome and that same end state.” The thing to keep in mind (and communicate to others) is that North Stars are not execution plans, and, as Greg says, should be done “in a way where people have permission to break them and change them, and challenge them.”

B. Adopt a portfolio approach

For Design organizations, there will always be more work to do than people to do it. So the trick is to figure out how best to focus efforts.

Kaaren Hanson cautioned against trying to do All The Things at once. “If you come in and you say, ‘We’re just going to do everything, we’re going to slow everything down,’ you are going to fail. But you can…look at this portfolio of initiatives, and say, ‘These two seem ripe for really having a bigger impact… And so we’re gonna put our points here’… and hope like hell at least one of them works.”

Or, as Katrina Alcorn said, “If you say yes to everything, nothing gets done.”

But then, how do you assemble this portfolio?

Choosing who you work with

When Greg Petroff was building the Design capability at GE, in order to focus their limited capacity on that which would have impact, his org would only work with two kinds of teams: “either they totally got us and they totally understood design, and they were all in, or they had tried everything and were failing and the business was about to die…And if you’re in the middle, we didn’t have the time for you. We were sorry.” The logic being, “if we could take a business that was struggling and make it successful, that had currency in that culture… And then the net promoters, …they were the ones who, if things were kind of tough, they could kind of support us in a moment.”

Rachel Kobetz had a similar approach: “It was a mix of finding … those people that could be champions with me, those people that could be the beacons. It’s really important to find, not just the individuals, but the projects or programs that can be the beacons to showcase how a new way of working yields better outcomes.”

Short-term gains within a long-term frame

Key to change management success is showing progress early. As Greg Petroff shared, “Senior executive attention span can be quite short. And so you have to find ways to show demonstrable quick wins and benefit, while leaving room for the things that are actually more substantive and impact-driven, that are going to take more time.” Rachel Kobetz cautioned that, “Sometimes, you know, leaders, they are charting the vision for tomorrow without delivering for today.” You need to balance, “be able to go deep, to be able to make sure that we’re building for today.”

Operating Mechanisms

For that longer-term frame, output (like launching a new product or service, or overhauling something in sore need of improvement), even with successful outcomes (more sign-ups, happier users) is insufficient. As Kaaren Hanson stresses, “Those operating mechanisms count so damn much.” By operating mechanisms she means evolving processes to account for customer-centered concerns, such as making sure customer experience measurements are part of business reviews. It also means “working with leaders across the business, including the CEO of consumer bank or the CEO of connected commerce or the CEO of wealth management, to ensure that design is sitting at their table,” making it a default expectation that design is included in the senior-most business conversations. She continues, “you have to get into the operations of the company, and companies have like a, heartbeat, which goes back to, what are the expectations for designers? What are the expectations for product managers? How are we bonusing people on this stuff? Like, those are all the operating mechanisms you have to infiltrate.”

C. Manage the relationships

Infiltrating operations requires working the relationships necessary to make change happen. And while it’s important to develop good relationships with the people within your organization, what these leaders stressed was how crucial it was to establish relationships with your cross-functional peers in product, engineering, marketing, and with executives and other stakeholders.

Cross-functional relationships

Kaaren Hanson has staffed her leadership team such that “every design leader that sits within a line of business sits at that [line of business’] CEO table.” She also expects that her design leaders are spending more time messaging and in meetings with their “product, engingeering, and data partners” than any other people.

And Rachel Kobetz, with whom we went quite deep on relationships, shared, “when I’m talking about the importance of the relationships, it’s where I spend a lot of my time. …Working across and working up…the whole company to make sure that there’s clear communication, there’s trust and we’re building relationships so that people understand what we’re doing.”

Make your partners successful

A recurring theme was to focus not on your own organization’s success, but, as Kaaren Hanson points out, “my job is to make you [my partner] more successful.” Greg Petroff echoed this, “you always wanna make sure that the, your partner is the one who gets the attention…We celebrated the wins, but the win was not us. The win was the business unit.”

Co-create outcomes before starting the work

A means for strengthening relationships, and to ensure your partners’ success is to co-create outcomes before doing the work. As Greg Petroff put it, “I’m all about co-defining outcomes. I think that’s a missing gap in software development. And I think a lot of product teams start without actually having a lot of clarity about what they’re trying to accomplish and they feel like the agile process will help them get there and it’s just nuts. And so you know, I am, I’m all about working with product teams early on to do things like Lean UX canvas work.”

Designers often like to talk process, but Rachel Kobetz suggests, “don’t harp on the process itself. Actually focus on the outcomes, and when you have shared outcomes together, you’re going to be set up for success.” By starting with shared outcomes, you can then engage in process discussions, because if “you’re aligned on shared outcomes, they’re going to be much more receptive and open to a new way of working, versus you just come in and say, ‘Everything you’re doing is wrong, and this is how we’re gonna do it.'”

Mixed maturity means varying reactions

One of the specific challenges of managing change, particularly in sizable organizations, is that you’ll have a different degrees of maturity in the different parts of the organization, and that leads to a range of reactions to that change. As Greg Petroff said, “it depends on the culture of the organization and it’s maturity and sometimes parts of the organization are great and others aren’t.”

Rachel Kobetz shared, “People handle change or evolution much differently. You have some people that are, like, ‘This feels awesome. I love it.’ You have other people…that say ‘change is the only thing that’s constant.’ And then you have other people that are like, ‘Wait, hold on, you moved my cheese, what happened here?'”

No judgment, maintain positivity, avoid toxicity

At the heart of change management is a recognition that things today aren’t as good as they could or should be (or why bother changing). TSo his leads to an unfortunate tendency to criticize the current state, but, as Kaaren Hanson learned, “Being judgmental is toxic…As someone who’s been in this field, we are incredibly critical of things. That’s our job is to be critical, right? But that’s not helpful when you’re working with other people, and you’re trying to drive change in an organization, because if you’re judgemental, it’s almost like you’re adding toxicity to relationship. So I’ve had to rein that way back.”

D. Communicate with intent

Every leader we spoke with addressed the importance of communications, and having a strategy, a plan. It’s not enough to do the work, it’s even not enough to make an impact. If you don’t make the effort to let others know about that impact, it might as well not have happened.

Katrina Alcorn shared how she’d been publicly blogging about the ongoing evolution of design at IBM.

Kaaren Hanson stressed how much time she’s spent with her leaders, having them share their stories with her initially, so she can provide feedback on the most salient points to then communicate out, “they’ll have those short stories and snippets that they can share with their executives in the elevator.”

Greg Petroff has built “shadow comms teams,” writing a monthly newsletter about all the things his team was doing. Tying to the prior theme, these newsletters showcased partners, “always a story about someone else in the organization that we promoted, ‘the SVP of product does this, and here’s the decisions that they made that were great around design work,’ because you want to celebrate them, too.”

Rachel Kobetz has found that the “the essence of it is just overcommunication.” She exploits a number of channels in getting her message out, “whether that is in a conversation with another executive in a meeting, and being able to have that moment to talk about the great work that the team is doing, or that our two teams are doing together. Creating a newsletter. Doing my own writing and pushing it out across the company. Whether it’s in town halls or, showcases, quarterly events, all of the different avenues you can take, you have to use those as opportunities to get the word out.” She concludes, you’re never done with that communication.”

Transparency

A judgment call that’s difficult for some leaders is knowing what to say to whom. As leaders, you have access to potentially sensitive information. That said, Kaaren Hanson stresses the importance of transparency: “if you’re not transparent about what you’re doing and why you’re doing it, it’s easy for people to read all kinds of other things into what you’re doing.” Daniela Jorge concurs, “something that I always aim to do as a leader, is providing as much transparency and context… I think it’s very easy when you’re in a leadership position to forget that you have access to a lot more information and context that a designer on the team might not.”

This transparency is essential for working with other functions, particularly when working toward shared outcomes. Rachel Kobetz proposes, “you instead open up that box and you create transparency in the process. You bring people in, you make them part of that process from day one, but then when you’re telling the story of it, you’re starting off on the foot of, we’re all aligned to shared outcomes.”

E. Maintain patience and perspective

As design leaders, we often have a clear view of where we want to go, and what it will take to get there, and the time it takes to make progress can prove quite frustrating. When I asked Daniela Jorge about how she helps her leaders who may be operating at a new level of seniority, she shared, “a lot of it is that we talk about perspective, patience, right? Figuring out how you’re influencing, figuring out how you can sometimes measure progress in small increments. Because the job that we do is hard, right? And especially because I think we are able to see what it should be and what it could be. And that isn’t always what is happening in that moment or in the short term. So, a lot of the time that we spend is just talking, regaining perspective so that folks don’t get discouraged.”

So get out there, and make some change!

If I were to assess the ‘vibes’ at the outset of 2023, it’s that there is a potential for fundamental shifts in the ways that businesses are working. This provides an opportunity for Design Leaders to proactively insert themselves into those ‘operating mechanisms’ (as Kaaren Hanson put it), and make some real change.

As this post suggests, change is hard. Its taxing, frustrating, and time consuming. But it’s also how we can make things better, for us, our teams, our colleagues, and our customers. If you’re signing up to be a design leader, you are signing up to make change.

(And if you’re interested in pursuing this theme further, I wholeheartedly recommend the new book Changemakers by Maria Giudice and Christopher Ireland. It provides clear actions you can take to realize the change you seek.)

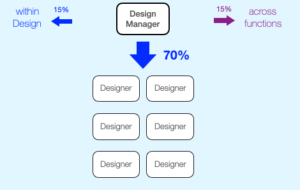

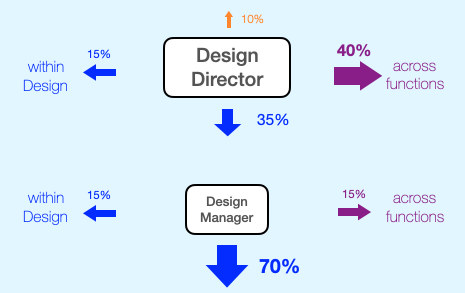

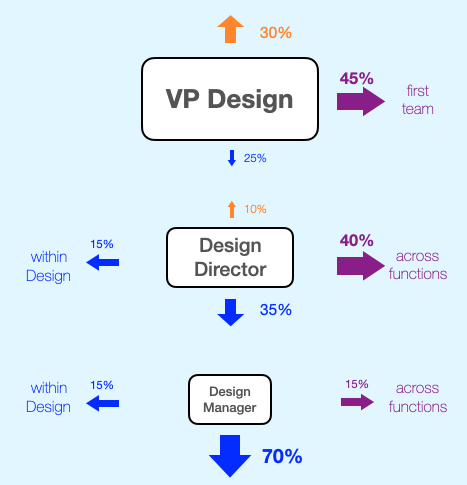

Their primary orientation is downward. They’re focused on getting the most out of the team the manage, making sure they’re delivering on expectations in terms of addressing problems and upholding quality.

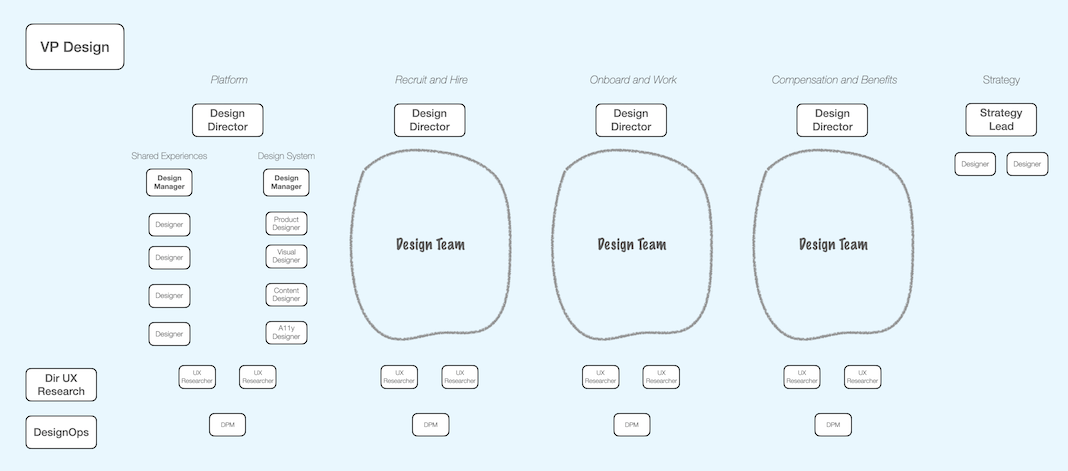

Their primary orientation is downward. They’re focused on getting the most out of the team the manage, making sure they’re delivering on expectations in terms of addressing problems and upholding quality. A Design Director’s primary orientation is sideways, and not only that it’s mostly outside of Design. An effective Design Director should be spending more of their time and energy working with non-design peers and other stakeholders than with any other kind of colleague.

A Design Director’s primary orientation is sideways, and not only that it’s mostly outside of Design. An effective Design Director should be spending more of their time and energy working with non-design peers and other stakeholders than with any other kind of colleague. And in terms of time spent, it goes even farther than that. The Design Team should be where a Design Executive spends the least amount of time. Their primary orientation is sideways, toward their executive peers. This is about planning and strategy for the organization, identifying opportunities for the business and how their coordinated teams can realize them.

And in terms of time spent, it goes even farther than that. The Design Team should be where a Design Executive spends the least amount of time. Their primary orientation is sideways, toward their executive peers. This is about planning and strategy for the organization, identifying opportunities for the business and how their coordinated teams can realize them.