TL; DR:

Critique and review are different. 🗣️Critique is simply about making the work better. Review is about assessing readiness for the next stage in the process.

Healthy critique requires ✨psychological safety✨. To make the work better means being able to discuss it openly, and frankly, warts and all. To do so in a constructive fashion requires that everyone involved know there will be no retribution for their work or commentary, as long as it’s offered in good faith, and in the interest of learning and doing better.

Perhaps the biggest barrier to conducting critique is 🧱structural: ‘making space’ for critique by finding time, getting the right people in the room, and ensuring that the time is well-spent. When done ad hoc, the effort necessary feels greater than the reward. So, make it an ✅operational priority, something that just happens as part of the flow of work.

This post is longer than usual, so here’s a Table of Contents to help you navigate:

Why critique matters

Critique is essential for UX/design practice. Like, literally: it’s at the essence of design.

“The practice of design is creation and criticism in dialogue with one another. And I think we’ve emphasized creation and completely lost the sense of criticism.”

Erika Hall, Finding Our Way

If you’re UX/Design org wants to deliver high quality work, constructive critique practice is crucial.

I am moved to write this post because in my work across literally dozens of design organizations around the world, all have struggled handling critique effectively. Either…

- They don’t conduct critique

- They conduct critique, but rarely

- They conduct what they call critique, but it’s actually review

Wait? There’s a difference between “critique” and “review”? Most definitely.

Critique is about making the work better.

Review is about assessing readiness for the next stage in the process.

What are the barriers to critique?

There exists an array of reasons why UX/Design teams either don’t critique, or do so rarely.

Understanding barriers

Don’t know what critique is. Many practitioners just don’t know what critique is. They didn’t experience it in school (perhaps, like me, they didn’t study design), and they haven’t experienced it in prior work. Some of those folks may now be team leaders, and critique just isn’t part of their practice or even vocabulary.

Confuse review for critique. These are teams that perform an activity they call ‘critique,’ but it’s actually review. Critique is simply about getting a group of people together to help someone improve their work. It shouldn’t be considered a stage-gate in a process, or an opportunity for senior people to unload on the less experienced people in the room.

Too often, what’s called ‘critique’ is more a form of review, not about improving the work, but APproving the work, determining if it’s ‘ready’ to move on to whatever the next stage of the process is.

Some signs that you are in a review, not a critique, include:

- non-UX/Design people in the room

- Very senior UX/Design people in the room, whose contribution is to pass judgment on the work, and may be seen as the final decision-makers in the room

- all the work shown is expected to have a high degree of polish/finish

The wrong people in the room. Defining “wrong people” can go a lot of directions:

- there are too many people (and thus too many voices, and it’s noise)

- there are too few people (and thus too few voices, and the feedback feels like direction, or not critique, more just an informal ‘uhh, what do you think of this?’)

- there are non UX/Design folks in the room (critique, in making the work better, should be limited to those with real expertise in how the work gets done, not just anyone with an opinion)

- there are people who don’t know the material under discussion (if you have to spend an inordinate amount of time bringing people up to speed so they can provide helpful questions and commentary, they might not be the right people to have in the room)

Focus on the wrong things. Critique should be about making the work better, which in turn should be all about the impact that this work will have. What are the goals, objectives, metrics, etc., that this design is meant to have. Ideally, what changes when it is ultimately released? Any other discussion is a distraction.

Mindset barriers

People may very well understand critique, and even wish to conduct it, but are wary of doing so, because of sensitivities around criticism, and how it is given, and how it’s received. Though understandable, such sensitivities hamstring critique.

Lack of psychological safety. If you remember one thing from this article, it’s that critique is about making it better, review is about assessing readiness. If you remember a second thing, it’s that healthy critique requires psychological safety. Psychological safety is the condition where people can try stuff, make mistakes, wander down blind alleys, push back, and, as long as it’s done with respect and in the interest of making the work better, those people have no fear of retribution.

Often, teams don’t conduct critique, since people are unwilling to ‘show their mess’ (work in progress), because they fear that showing anything that isn’t ready will expose them to undue criticism, performance issues, etc. Critique has to be a truly ‘safe space,’ or it will be rendered performative.

Uneven power dynamics. Too often, critiques are used as opportunities for senior team members to tear into the work of junior team members. Some even think this is the point, in ‘steel sharpens steel’ kind of way. But if there is not a healthy dynamic, criticism from senior people can just come across as attack, the junior people experience a kind of workplace trauma, and subsequently do anything to avoid being put in that situation. This is all exacerbated if the senior people never have their work subject to critique, so it only ever goes one way.

Trouble distinguishing the work and the person. Critique is about the work. But if it’s not handled well, it can feel like it’s about the person. Sometimes this is about the nature of the feedback given, “You should…” or “Why didn’t you…?” Sometimes its because the presenter only provides one solution or idea, and so if that idea doesn’t fly, it feels personal. If the presenter provides options or alternatives, then it’s more straightforward to make it about the work.

Discomfort with the word ‘criticism’. I’m hesitant to bring this up, but for decades now, I’ve heard people take issue with the word “critique” or “criticism,” with the idea that it encourages negativity.

Operational barriers

Because it occurs outside the flow of typical product development practices, critique can feel like a ‘nice-to-have,’ and nice-to-have’s rarely happen, because people already feel overburdened with their ‘must-do’s. If critique is seen to add effort (and with little direct benefit), it won’t get done.

Finding the right time with the right people. In my experience, this is probably the most acute barrier to conducting critique. When done in an ad hoc fashion, it requires scheduling well in advance in order to get on people’s calendars. And when competing with other demands on time, often loses to work that feels more crucial.

Setting the context so that the critique can be useful. I’ve supported teams where a third of the critique time is taken up ensuring people have enough context so that they can provide helpful feedback.

A Plan for Critique

To address these barriers, I’ve created a plan for setting up critique within a design organization. And this is very much a plan not the plan—what works in your org will likely be different. I’m hopeful that the principles and frameworks give you a place to start to make it work for you.

Principles / requirements for critique

Psychological safety. Stated above, worth restating. It must be made explicit that critique is not an environment for personal judgment, retribution, performance, etc.

All participants must be up for being critiqued (no commentator-only roles). This begs the question, “But what about more senior leaders, Directors and VPs?” And the answer is: they’re welcome to attend critiques as silent observers (in fact, it’s encouraged), but they do not get any say in the critique, unless they put their work up for critique. And remember: any work can be critiqued. It doesn’t need to be design effort. Christina Goldschmidt, VP Design at Warner Music Group, shared on Finding Our Way how she embraces her work being critiqued: “[it may be a] strategy on something or it might be a flow on something or something like that. Or it might be an approach to something, but so that they can actually give me input.”

Fits within people’s working schedule. Critiques should not be ad hoc, but have regularly scheduled time dedicated to them, so people can plan accordingly.

Manageable. There’s a bit of a Goldilocks-ness to critique—the subject matter should be ‘just right,’ to allow for a critique that isn’t too long, too short, too complex, too basic. It may take a few cycles to figure out just-right-ness.

Prepared. Anyone presenting their work must be prepared. Critique is a gift to the practitioner, an opportunity to make their work better thanks to the attention and feedback from their peers. Respect those peers by being prepared, so that you can make the most of your time together.

Good critique requires stable structure

At the core of critique are two structural elements:

- Regular critique pods

- Regular critique hours

Regular Critique Pods

A challenge for critique is the amount of context necessary in order to get quality feedback. I’ve seen orgs where critique happened across all design, and where a third of the time spent was just getting everyone enough context to understand the design problem.

To address this, consider creating Critique pods of 4-5 people. You likely already have people already grouped in some kind of fashion (reporting to the same manager; working on the same product), so just use that. If you don’t, well, just figure out what works for now, and they’ll likely shift and evolve for a while.

Regular Critique Hours

Another challenge for establishing critique is simply to find the time to do it. It’s important that critique happen frequently enough that it doesn’t feel like a big deal, but just part of the process.

To address this, consider setting aside 2 hours a week for critique, at the same time each week (e.g., 4pm-6pm UK Time every Wednesday). Everyone blocks this time off in their calendar and knows it is when critique happens.

This time block holds across all critique pods. Benefits of having critiques happen at the same time includes:

- Two pods, working on adjacent or related material, can have a co-critique

- The VP, Directors, and others who aren’t part of specific pods know when they can join specific critiques, which is great for leadership visibility (though: if leadership is not putting themselves up for critique, then they are to be silent observers of the process)

What to Critique?

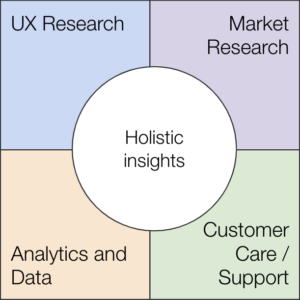

There’s some question as to what is useful for critique. This illustration from the book Discussing Design depicts the ‘sweet spot’ for critique:

Critique shouldn’t only be about detailed designs. Workflows, wireframes, content directions, etc., are all good subjects for critique, as all are designed to deliver on some objective.

Conducting Critique

Every critique session should have at least 2, and as many as 4, critiques within it. Rotate through the pod to make sure everyone is getting critiqued every couple weeks.

Each critique takes 30 to 60 minutes, depending on how much material there is to cover.

Discussing Design provides this simple framework for approaching critique:

Before Critique

The Practitioner should spend ~30 minutes before the critique to set it up. They should create a board (in Figma/Figjam or Miro) with the material they want to walk through, have prepared a statement about the objective(s) they are trying to achieve, and prepare any other context necessary to bring people up to speed (the business problem, the user type or specific target persona).

Early / Mid / Late

When preparing for critique, it’s important to situate the design work in the overall story of the project. If Early in the project, direct people away from the details of the solution, and more toward the matters of structure, flow, shape, message. If in the Middle of the project, have people critique in detail. If Late in the project, discourage commentary about structure and flow in favor of final fit and finish, adhering to standards, and the specific use of language.

The Critique (figuring about an hour total, but will vary depending on breadth and depth)

Presenting – 10-15 minutes

After folks have gathered, the Practitioner presents their work, starting with the Objective statement and any other context. Then they go through the designs, articulating why they made key decisions.

Clarifying questions – 5 minutes

Once the design has been presented, the Critiquers ask any clarifying questions they have, to make sure they understand exactly what is being addressed by the designs.

Writing down feedback – 10 minutes

On the critique board, Critiquers write virtual stickies to capture their thoughts about the work, in context. The feedback should be rooted in a) the objective and b) design standards. The amount of time for writing down should be relative to the amount of work shown, but it is important that it is timeboxed.

Feedback should be both positive and negative. It’s okay for the feedback to be mostly negative (we are trying to improve the work), but it’s helpful to call out what is working (and should be left as is).

When a Critiquer places their thought, if another Critiquer agrees or disagrees with it, place a 👍 or a 👎 on the sticky to indicate that.

As Critiquers are placing their thoughts, the Practitioner is reviewing them, and making their own notes in terms of follow up questions to ask.

It’s essential that this first round of feedback is done silently. If you go immediately to oral feedback, that preferences folks who are more comfortable speaking out, who ‘think out loud.’ Reflective written feedback enables greater participation from Critiquers.

For strong guidance in how to give good written feedback, read: Asynchronous Design Critique: Giving Feedback. The advice holds even for synchronous, written feedback.

Feedback Don’ts

- Do not provide “preference” based feedback (“I like…”)

- Do not offer solutions in the feedback (“Move this to the right”)

- Make assumptions—if you’re not sure about something, ask a clarifying question

Feedback Do’s

- Connect comments to objectives or design standards

- Bring a perspective (either yours, or a persona’s)

- Point out (what seems to be) the obvious—it may not be so to others

- Indicate your level of severity. For example, the emoji model suggested by the Giving Feedback article:

- 🟥 a red square means that it’s something potentially worth blocking

- 🔶 a yellow diamond is something where one can be convinced otherwise, but it seems to that it should be changed

- 🟢 a green circle is a positive confirmation.

- 🌀 a blue spiral is for either something that uncertain, an exploration, an open alternative, or just a note.

Discussing feedback – 15-20 minutes

The Practitioner walks back through the work, and the critique comments. They ask for clarification on anything that they don’t understand. For any sticky with an 👎, ask the person who disagreed to explain why.

The Practitioner should not defend their work, nor revise/refine based on feedback in the moment. All the Practitioner needs to do is take the feedback in, and make sure they understand it.

To understand the ‘weight’ behind the feedback, conduct a ~3-minute voting session, where the Critiquers can vote on the (3-5, depending on the amount of commentary) items that they feel most strongly need to be addressed. This helps the designer understand where to focus their efforts in revision.

Additional Resources

Web searching will turn up a bunch of good stuff on how to conduct critique. Here are a few resources to get you started.

- Discussing Design; still the best (only) book devoted to the subject

- Asynchronous Design Critique; in our world of remote work, I found this super helpful

- Design Critique Culture

- Practical Design Critique; a very long piece, lots of good stuff in here